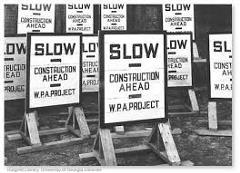

The Great Depression made its mark on nearly every aspect of American life and business. Construction was no exception. Public works dominated, as a primary strategy of President Roosevelt was to provide jobs and restore economic health through New Deal policies.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was the largest and most ambitious New Deal agency. It employed millions of people to carry out public works projects, including the construction of public buildings and roads.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was the largest and most ambitious New Deal agency. It employed millions of people to carry out public works projects, including the construction of public buildings and roads.

The WPA's initial appropriation in 1935 was for $4.9 billion (about 6.7 percent of the 1935 Gross Domestic Product).

The program built traditional infrastructure such as roads, bridges, schools, courthouses, hospitals, and more. Projects included 40,000 new and 85,000 improved buildings. These new buildings included 5,900 schools; 9,300 auditoriums, gyms, and recreational buildings; 1,000 libraries; 7,000 dormitories; and 900 armories.

Total expenditures on WPA projects through June 1941, totaled approximately $11.4 billion. Over $4 billion was spent on highway, road, and street projects;

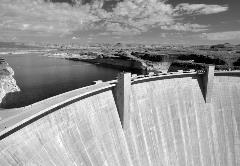

Nothing Short of Monumental

Perhaps the most monumental concrete WPA project—and one of the century's most iconic—was Hoover Dam.

Perhaps the most monumental concrete WPA project—and one of the century's most iconic—was Hoover Dam.

Thousands of workers flocked to Black Canyon on the Colorado River to build the largest dam of the era.

The dam required massive amounts of concrete. A total of 3.2 million cubic yards of concrete was placed before pouring ceased on May 29, 1935. Another 1.1 million cubic yards was used for the power plant and other works. There is enough concrete in the dam to pave a two-lane highway from San Francisco to New York.

Research Drives Strength and Durability

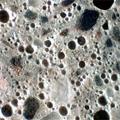

The 1930s witnessed one of the most profound technical advancements for concrete of the century: Air entrainment.

T.C. Powers, PCA's head of research, discovered air entrainment as a method of making concrete less susceptible to damage from freeze-thaw cycles, a problem in northern climates.

Air-entrained concrete contains billions of microscopic air cells in each cubic foot of material. These air pockets relieve internal pressure on the concrete by providing tiny chambers for water to expand into when it freezes. It significantly reduces concrete’s tendency to crack and spall during freeze-thaw cycles.

Air-entrained concrete contains billions of microscopic air cells in each cubic foot of material. These air pockets relieve internal pressure on the concrete by providing tiny chambers for water to expand into when it freezes. It significantly reduces concrete’s tendency to crack and spall during freeze-thaw cycles.

Air-entrained concrete is produced using air-entraining portland cement, or by the introduction of air-entraining agents as the concrete is mixed on the job. The amount of entrained air is usually between four and seven percent of the volume of the concrete, but may vary as required by special conditions.

Other PCA research focused on best practices in concrete construction. In 1931, the introduction of internal vibrators as a means of placing concrete lead PCA to assess how the practice affected strength. Researchers found that internally vibrated concrete was 2,000 pounds per square inch (psi) stronger than hand-placed concrete with the same cement content.

The vibration itself did not make the concrete stronger. But it did allow workers to place stiff concrete mixtures made with less water and therefore a lower water-cement ratio, which increased strength significantly.

Other major research initiatives in the Thirties explored the effects of concrete admixtures and conducted field tests of soil cement.

Treval Clifford (T. C.) Powers served in PCA’s Research Department for 35 years, from 1930 until his retirement in 1965.

Mehren Becomes First Staff President

Edward J. Mehren joined PCA in 1931 as its first staff president. Previously he served as the editor of Engineering News-Record, the construction industry trade magazine still published today.

For the 15 previous years, the office of PCA president was an unpaid position held by a succession of member company executives. A general manager working closely with the honorary president handled day-to-day management.

Mehren served until 1937. He was succeeded by Frank T. Sheets, who was president until his death in 1951. Sheets was previously the Illinois State Highway Superintendent and Chief Highway Engineer prior to joining PCA in 1933.